Spring-driven clocks were developed during the 15th century, and this gave the clockmakers many new problems to solve, such as how to compensate for the changing power supplied as the spring unwound.

The first record of a minute hand on a clock is 1475, in the Almanus Manuscript of Brother Paul.

During the 15th and 16th centuries, clockmaking flourished, particularly in the metalworking towns of Nuremberg and Augsburg, and, in France, Blois. Some of the more basic table clocks have only one time-keeping hand, with the dial between the hour markers being divided into four equal parts making the clocks readable to the nearest 15 minutes. Other clocks were exhibitions of craftsmanship and skill, incorporating astronomical indicators and musical movements. The cross-beat escapement was developed in 1585 by Jobst Burgi, who also developed the remontoire. Burgi’s accurate clocks helped Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler to observe astronomical events with much greater precision than before.

The first record of a second hand on a clock is about 1560, on a clock now in the Fremersdorf collection. However, this clock could not have been accurate, and the second hand was probably for indicating that the clock was working.

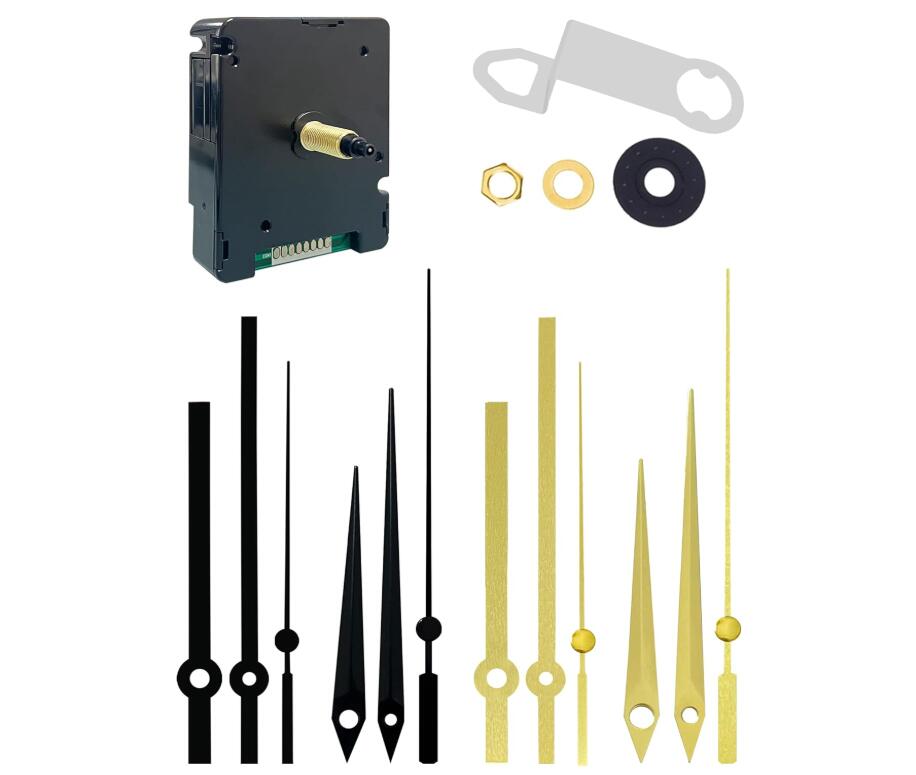

- Sweep clock movement

- Clock hands

- High torque clock movement

- Skeleton clock movement

- Radio controlled clocks

- Pendulum clock movement

- 24 hours clock movement

- Tide clock movement

- DIY clock movement

- Round clock movement

- Quartz clock movement

- Clock inserts

- Watch inserts

- Clock parts

- Clock dials

- Wall clocks

- Plastic clock movements

- Toy clock movements

- Hook clock movement

- Alarm clock

- Clock movement

- Movements package

- Clock hands catalog

Sitemap Admin Powered by: hkwww.cn

Tel: 86-769-85532891 E-mail: talent@hengrongclock.com.cn http://www.clockmovements.cn

Keywords: clock movement, clock parts, clock hands, clock mechanism, clock accessories, cuckoo clock, alarm clock, insert clock